When I began work on my novel I knew as little about Brazil as the next foreigner. I'd once stopped over at Rio de Janeiro for three days on a flight to Africa, an instant course in cliches of Carnival, samba, beach and jungle. I'd another impression that harked back to my South African childhood, when the country was still tied to England.

Every month there arrived from London an adventure magazine for boys, its pages filled with the glories of Empire and conquests of its heroes. Among them, explorer Percy Fawcett who was most often depicted in a tiny canoe paddling past the gaping jaws of an anaconda. Colonel Fawcett went in search of a fabulous Lost City in Brazil and vanished forever in Mato Grosso. The intrepid fortune hunter lived on in the imagination of boys  1ike myself who scoffed at the idea that an Englishman had been killed by headhunters and pictured our champion sitting on a golden throne in E1 Dorado.

1ike myself who scoffed at the idea that an Englishman had been killed by headhunters and pictured our champion sitting on a golden throne in E1 Dorado.

1ike myself who scoffed at the idea that an Englishman had been killed by headhunters and pictured our champion sitting on a golden throne in E1 Dorado.

1ike myself who scoffed at the idea that an Englishman had been killed by headhunters and pictured our champion sitting on a golden throne in E1 Dorado.

Living in a day when we still saw the world divided into two parts — those who belonged to the British Commonwealth and those who didn't — I naturally considered Fawcett to be the discoverer of the Brazilian interior. Before his time, I believed, no one dared venture there except the denizens of the impenetrable forest.

I remember drawing a huge map of Brazil, days of painstaking work with pen and India ink, with every known river and a myriad tributaries. I marked my hero's route to "Point X" where he disappeared. The map won me a coveted star from my geography teacher, Miss Kane, and a vow to "find" Fawcett. Little did I know that many years later I would visit some of the very places explored by Fawcett that remained as deserted as when he first set eyes on them half a century earlier.

As happens with boyhood fantasies, somewhere along the way I left Fawcett behind and got on with my schooling. Then came the real world and a brief and wretched experience as a law clerk. My father knew I wanted to be a journalist but warned that before I wasted my life as a writer, I should get a safe "billet," a favorite word of his. He suggested a career in accountancy or better still, a job with the Johannesburg city council, where I would be guaranteed a pension. (A chilling prospect for a seventeen-year-old!) I tried law but after a couple of years of hounding debtors and licking stamps, I abandoned this course.

Then came another round of fantasies with a disastrous attempt to go into business for myself. I founded the Lincoln Swift Organization, an odd mixture of cane furniture factory, pottery distributor, and missing persons bureau. It survived three months. At last, in an act of desperation, I literally threw myself at the feet of the manager of the Johannesburg Star and asked for a job. I got it.

Between daydreams about Fawcett, I'd been writing stories from the age of ten. I was seventeen when I penned my first novel, a three-hundred page saga of teenage angst in a small town in South Africa. Unpublished, I included it with my application to the Star and to my everlasting gratitude, the editors decided to take a chance on me. Three weeks after joining the paper, my name was in print for the first time beneath an article on the editorial page: Happiness is an Unprejudiced Mind.

Between daydreams about Fawcett, I'd been writing stories from the age of ten. I was seventeen when I penned my first novel, a three-hundred page saga of teenage angst in a small town in South Africa. Unpublished, I included it with my application to the Star and to my everlasting gratitude, the editors decided to take a chance on me. Three weeks after joining the paper, my name was in print for the first time beneath an article on the editorial page: Happiness is an Unprejudiced Mind.

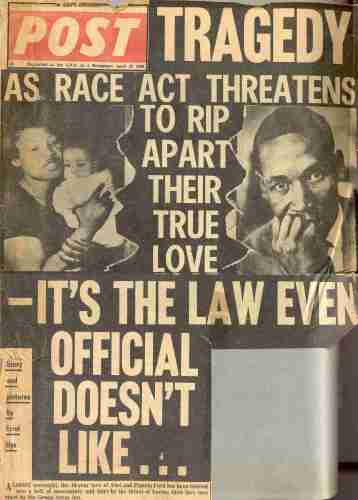

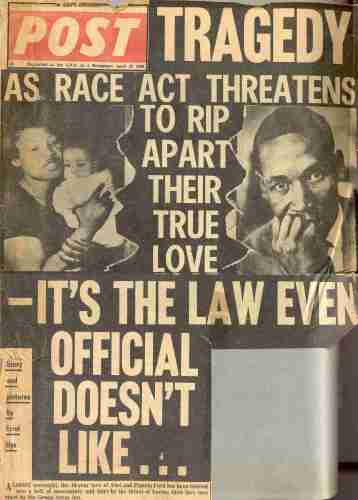

My career as reporter, features writer and editor spanned seventeen years on three continents. From the Star I went to Post, a newspaper serving the black and mixed-race communities of South Africa. Then to England and the South-East London Mercury, a London weekly; in London I joined Reader's Digest returning to South Africa, where I became editor-in-chief. In 1977, I came to the magazine's headquarters at Pleasantville in the United States. My transfer couldn't have been more propitious.

years on three continents. From the Star I went to Post, a newspaper serving the black and mixed-race communities of South Africa. Then to England and the South-East London Mercury, a London weekly; in London I joined Reader's Digest returning to South Africa, where I became editor-in-chief. In 1977, I came to the magazine's headquarters at Pleasantville in the United States. My transfer couldn't have been more propitious.

years on three continents. From the Star I went to Post, a newspaper serving the black and mixed-race communities of South Africa. Then to England and the South-East London Mercury, a London weekly; in London I joined Reader's Digest returning to South Africa, where I became editor-in-chief. In 1977, I came to the magazine's headquarters at Pleasantville in the United States. My transfer couldn't have been more propitious.

years on three continents. From the Star I went to Post, a newspaper serving the black and mixed-race communities of South Africa. Then to England and the South-East London Mercury, a London weekly; in London I joined Reader's Digest returning to South Africa, where I became editor-in-chief. In 1977, I came to the magazine's headquarters at Pleasantville in the United States. My transfer couldn't have been more propitious.

In 1978 because of my background and the Digest's long-standing relationship with James A. Michener, I was assigned to work with the writer on his South African novel, The Covenant. My two years with Michener convinced me that were I ever to be an author I would have to make a total commitment to writing, not pecking away at manuscripts in the dark of night but out in the open. At the end of 1980, I resigned from the Digest to begin work on Brazil.

BRAZIL - The Making of A Novel - Part 1

No comments:

Post a Comment